In 2009, Steven & I started an agency.

It was in the afterglow of the of Apple’s iPhone debut, and our agency’s toddler years were set against the backdrop of what felt like a technological summer of love. “Apps” became democratized, interfaces became richer, intuitive touch gestures became a primary way to interact with devices, and a new wave of startups materialized in the wake of a global recession.

A lack of precedence, constraints, tools, and accepted best practices created the conditions for a wild spectrum of work. For both better and worse. Often, the energy and momentum of the time turned everything into a nail that suffered excessive hammering - an inevitable byproduct of any compelling new technology. On the other end of the spectrum, you could find wonderfully imaginative work being created, some of it resembling more art than technology.

Like other agencies we respected, we saw an opportunity to deliver unique and creative work, while helping our clients adopt the latest technologies thoughtfully.

But this story doesn’t begin with technology. It begins with something analog, something that has existed since long before the iPhone, the Internet, or even the transistor. It begins with the notebook.

The Notebook

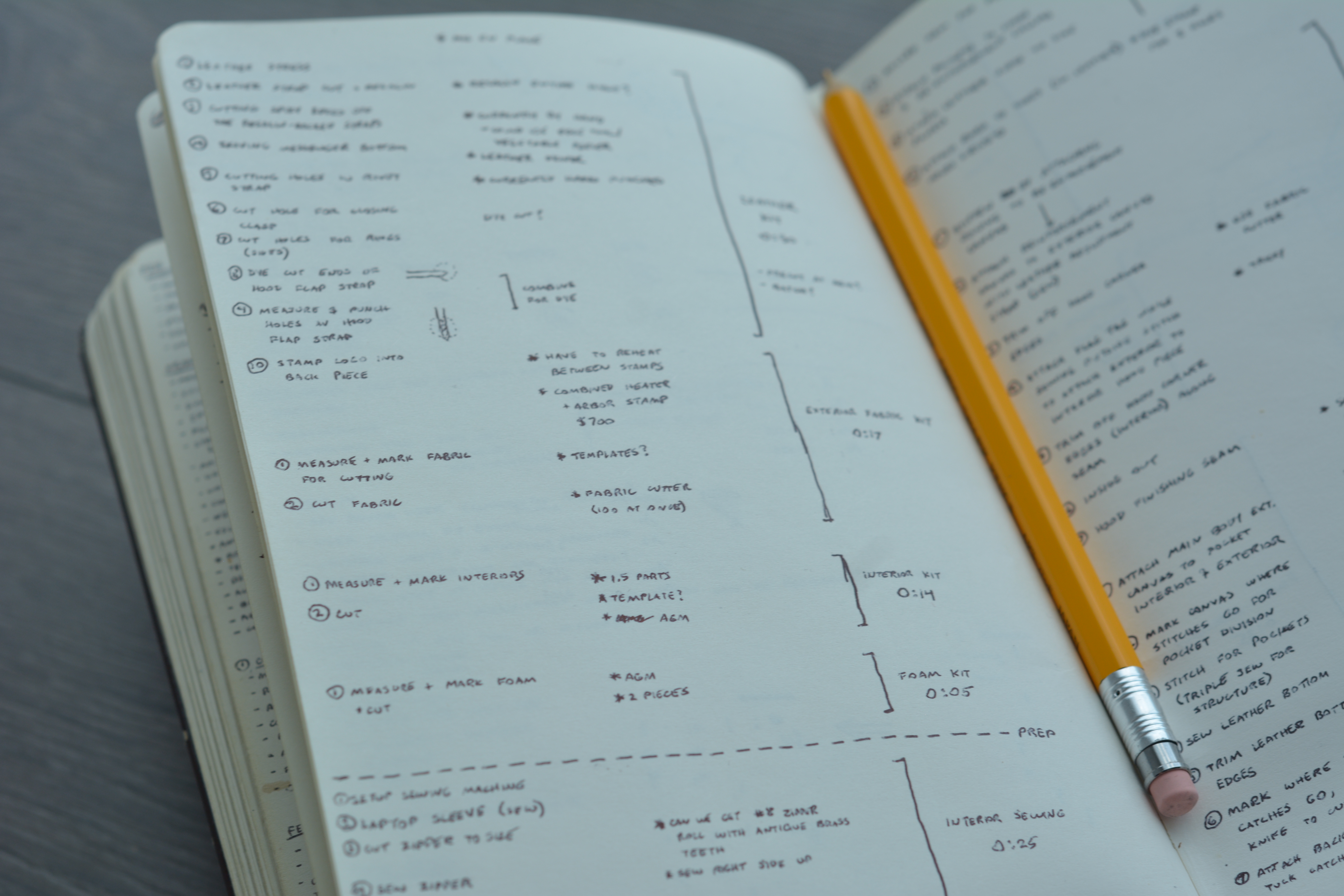

Steven & I both used notebooks long before we met. When we began planning our agency in 2008, we would loiter at Denny’s, and our notebooks were our tool of choice to cobble together a shared vision of the future. From that moment onward, our notebooks became the bedrock of thoughts, ideas, and strategies upon which we built our company. They were always with us; at home, at cafes, in planes & trains, and in particular, at meetings.

Sometimes, our clients found it peculiar that we brought notebooks to meetings. We were the guys they were counting on to usher them into the digital age, and upon meeting, we would reach into our bags and pull out state-of-the-art…notebooks.

This simply seemed like the most practical way for us to take notes at client meetings. Especially then, before video calls became the norm, the sales and creative process (or at least, the perceived creative process) largely hinged on face-to-face meetings. Having a pair of laptops plopped on the table between us and our client felt tactless, and also emblematic of what we didn’t want to convey.

In these meetings, a physical notebook is obviously less intrusive than a laptop. But there are also more subtle benefits that came with taking notes in our notebooks.

Because Steven & I are slower to write than we are to type (and because we are not stenographers), we do not transcribe verbatim what we hear during a meeting. When we jot down notes with pen and paper, the limiting constraint of speed forces us to be much more frugal with our note-taking. We have to make a decisions as to what are the most important takeaways. This decision-making happens quickly and is nearly instinctual.

(These instincts don’t stem from a reservoir of pre-existing subject matter expertise we have. We subconsciously make decisions about what is important based on our perception the client’s body language; changes in their emotional resonance, the tenor of the their voice. Observing such behaviour is easier when there isn’t a screen in front of us. And this applies in reverse too - clients are more likely to exude such body language if they aren’t talking to a laptop.)

In the hours or days following a meeting, we revisited our scrawled notes. Then we figured out what’s next. We brainstormed ideas and came up with plans, which we wrote down next to our meeting notes, because that’s what was easiest (the notes were already right there, no context change was needed). Our notebooks quickly filled up with notes, ideas, action items, and sketches.

Obviously there are issues with this process, which presumably don’t need to be discussed here. They’re the same issues that would make most people today (ourselves included) choose to use a notes app over pen & paper (if pen & paper were considered options at all): digital notes are faster to write, easier to find, and easier to organize.

In particular, that we could not share our notes with one another - and in turn, create a shared context - became too important to ignore. So in 2013, we decided to create our own collaborative notes app. We affectionately code-named it "Blackbook" - an homage to the black notebooks we dotingly carried around.

Blackbook Begins

We shape our tools and thereafter they shape us. These extensions of our senses begin to interact with our senses. These media become a massage. The new change in the environment creates a new balance among the senses. No sense operates in isolation. The full sensorium seeks fulfillment in almost every sense experience.

Since our early days, we've had a habit of building little toy apps for ourselves on the side; a dashboard to track our company’s vitals and a digital portal our clients to interact interact with us ("Client Care”) are such examples. Our client projects were challenging and fascinating, but truthfully, these moonlighted side-projects were more fun.

Did we need to build a notes app? No. The landscape for note-taking apps was not as saturated as it is now, but there were still many options. Evernote was the incumbent, with a few other indie apps emerging at the time. Even Google Docs would have met our functional requirements.

There’s no rational explanation for why we decided to make our own notes app. I could retrospectively invent a justification gift-wrapped in market-analysis jargon, but the honest truth is that we just wanted to. We had both spent a fair amount of time thinking about notes and notebooks, and the prospect of putting on our adventure hats and exploring this curiosity in a purposeful way appealed to us. There are, after all, worse reasons to do things.

We felt we had the capability to make something that met our functional requirements and that we enjoyed using. Our wish list was simple. We wanted something minimal, with the focus being on writing and collaboration. And on a thoughtful interface; this was a tool that we intended to use and look at everyday.

We got to work, and produced a functioning proof-of-concept relatively quickly. That was the easy part. As soon as we possibly could, we started using it to write real notes. It worked fine, but wasn’t particularly special in any way except that it was our own (which isn’t nothing). The next step - making it work really well - was the hard part.

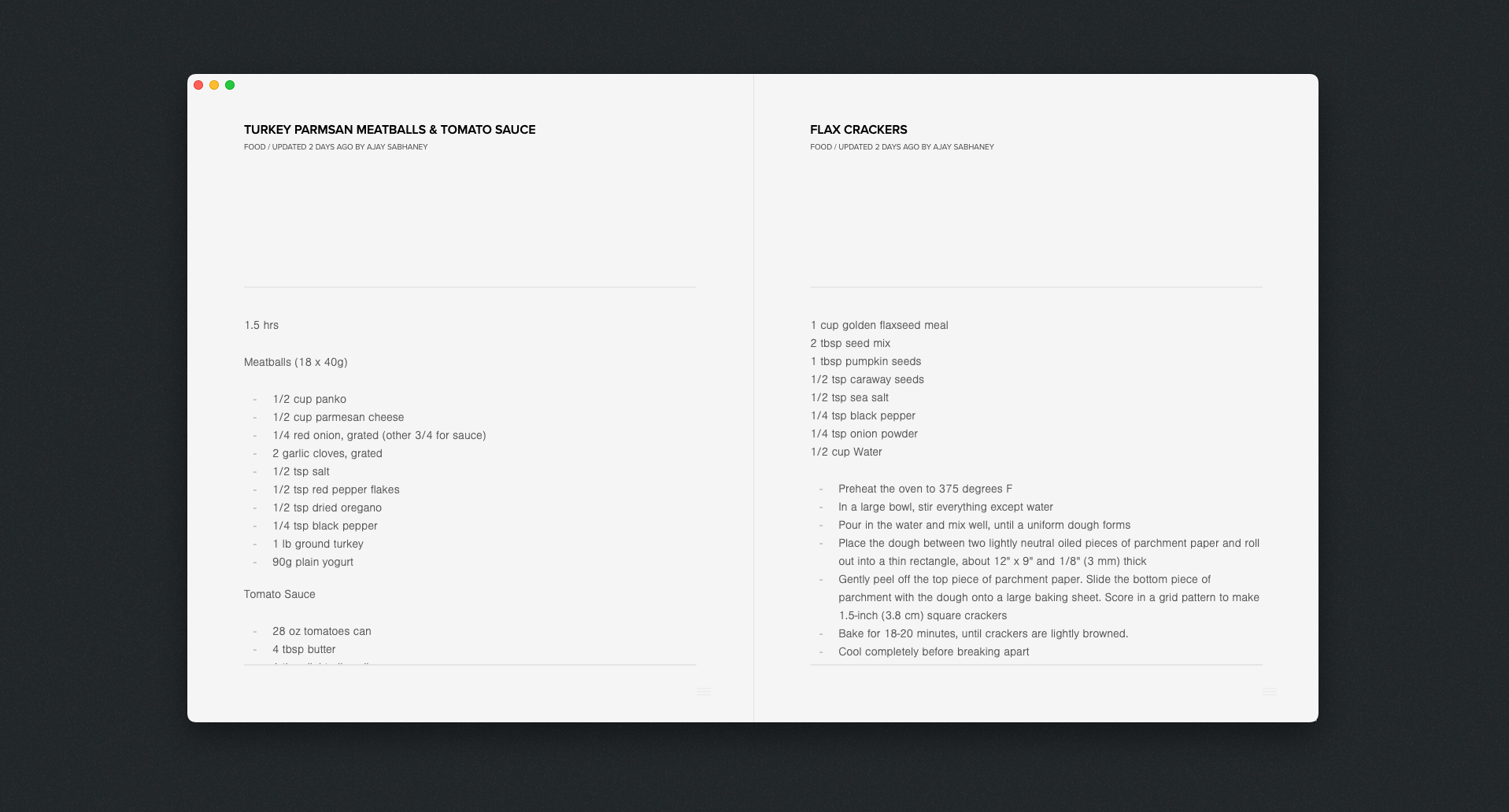

One day while working on Blackbook, Steven carried out an experiment. Instead of showing one note on the screen at any given time (as one would expect), he halved the width of the note, the result being that you could now see two notes at once on the screen, side-by-side. It effectively made the app look like a notebook.

It was a small change to the code, but it produced something that was addictive to look at. Reverse engineering a visceral reaction is the job of the designer, though it’s not an exact science. What precisely were we reacting to? Was it that the change in aspect ratio made the aesthetic pleasing? Perhaps it was simply that years of staring at books and magazines had etched a comforting familiarity into our psyche.

More importantly, this facing-page experiment changed how we thought of our app altogether. We began to see Blackbook as a notebook app instead of a notes app.

Perhaps this shift in thinking was meaningless, naive or gimmicky. But this was a hobby project. There were no deadlines. Our goal was not differentiation for differentiation’s sake. Nor at this point was it commercialization. We could ride an idea on horseback, letting it take us where it may, once in a while gently pulling back on the reigns. The only constraint was that Blackbook had to be useful and easy-to-use1.

There were times when we weren’t fully confident in the facing-pages approach, because it was a different form-factor than the mainstream note-taking apps already out there. But then again, the note-taking apps already out there were different than the experiences we had always enjoyed with our notes in the real world. Just because those apps came first, we didn’t feel that alone should get to define the form-factor of every other note-taking app thereafter.

We were nowhere near done, but we were intruiged by where we found ourselves. Our app and our notebooks embodied different forms and looked different from one another, but in spirit, Blackbook felt like a natural extension of its physical counterpart.

Interlude: Who Cares?

Before we dismiss Steven & myself as sentimental luddites pathetically rolling out the red carpet for skeuomorphic design, I want to briefly muse about some of the valuable traits of notebooks, and why they matter.

For example:

- Notebooks are minimal by nature. There is no distraction that will relieve you from the blank page laying in front of you, taunting you. There is only one thing one can do to overcome the unsettling feeling that comes with an empty canvas: to write, to sketch, to create.

- Notebooks incentivize free form expression. The lack of structure invites the mind to wander. It allows you to doodle in between paragraphs or to jot down sentences at a peculiar angle to fit in the negative space of a page. Being constantly presented with the opportunity to digress from the routine allows us to build a muscle in using form to think differently about what we want to express.

What’s notable is that these benefits were not planned, they are simply inherent to the form factor of physical notebooks. I imagine that if these benefits had been planned as “features”, the outcome would have been gobbledygook. The beauty of the physical notebook is that it is not prescriptive or pedantic about how one should use it, and in that regard, it is infinitely scalable.

There is one trait in particular that I want to hone in on, because it’s a characteristic that has been largely ignored in the era of digital note-taking:

Notebooks are bound.

While each of your notes may be independent from one another, the notebook itself provides a connective tissue that force notes to be co-located. In the real world, we become attached to our notebooks, rather than to individual notes.

The chronology of the pages reflect our own evolution, so we can revisit old notes and notebooks to bemuse who we once were and how we once thought. We associate memories, feelings, and phases of our lives with each notebook.

We serendipitously find new ideas in old pages, sometimes for no reason other than that two unrelated thoughts co-habit the same page, colliding together to incite a spark, like two neighbours who become friends while tending to their gardens.

All this makes the notebook feel like more than the sum of its parts, yielding something that feels deeply personal. There is a satisfaction to using a notebook this that isn’t rooted in an obvious function.

So that’s all fine, but does that mean we should attempt to translate each of these characteristics into a digital context? Of course not. That’s how gimmicky products are born.

For example, take that bit about the freedom of being able to jot down thoughts at an angle in the negative space of the page. It would be quite difficult to recreate the nature of that opportunity in the context of Blackbook (unless perhaps our app was only for tablets). Any time your brain requires you to translate an unstructured impulse (the messy language of our minds) into a structured action (the language of software), it’s too late - the momentum of the idea is gone. A whim is fleeting - it can exist much more easily when you’re not asked to codify it. This is the friction tax that software often imposes on us when we want to freely express whatever we want, however we want.

On the other hand, that bit about the notebook being larger than the sum of its parts? Well, we already had facing pages. We felt we could extend the metaphor one turn of the dial by adding “page flip” animations as well. If we could do it just right - if we could do it subtly, tastefully, fluidly and without making it obtrusive - then perhaps we could recreate that feeling of the connective tissue.

Blackbook, Continued

Time passed, and our circle of life continued. Agency work during the day, Blackbook by night.

We liked using Blackbook, which tricked us into writing more. Our little app had become our de facto repository for client briefs, meeting notes, and half-formed thoughts. We even used it as our primary medium for writing and storing our personal notes.

Using the app daily also made us hungry to improve it just as frequently. We added many features, while trying to retain the minimalism that had initially compelled us. It’s easy to start with a minimal interface, but much harder to keep it that way.

Here are a few of the improvements and additions we made:

- Mobile support so we could use Blackbook on our phones. Obviously this had to be done without facing pages (lack of screen real estate), but we retained the page-flip animation which paired well with swiping gestures.

- Collections, which was our way of letting you organize notes into folder-type structures. This in itself was not novel (nor did it need to be), but we also introduced a feature called Cover Pages that we particularly liked. Cover Pages were not really “pages” you could write on, but system-generated pages that acted as dividers between Collections - much like the beginning of a new chapter of a book. This was neat because it allowed you to flip from one page to the next, even if it meant going from one collection to another, while providing you with an obvious and pleasing visual cue that you were doing so.

- Table of Contents, which was just a standard navigation. We took some artistic liberties here that would be completely unpractical in a commercial product.

In addition, we also added special kinds of pages to supplement ordinary pages, or “Note Pages”, as we began calling them. In particular, we added "Media Pages", which allowed us to create moodboards. This allowed to upload images and have them display in a masonry-style grid. We added this feature because too often, our client briefs felt incomplete without moodboards and visual inspiration. Having a Media Page and a related Note Page side-by-side became a natural way for us to synthesize and organize ideas.

I don’t want to misrepresent what we built. Blackbook was not perfect. Even with all these additions I mentioned, there was no hiding behind features - our app was less powerful than most of the incumbent note-taking apps. Not that we really cared, because Blackbook was fun to make and to use, which ultimately had been the point.

What was truly most impressive about Blackbook was just how fast it was. It was impressively zippy, even on our (by today’s standards) clunky, palaeolithic MacBooks (circa 2009). You could hold down the arrow key on your keyboard, and pages would just glide effortlessly across the screen.

This wasn’t a happy accident. Performance was what we had spent most our time working on, because it had to be fast. If it was anything less than silky smooth, then all the decisions we made about facing pages and page animations really would be gimmicky and stink of naivety. But because the app never lagged, those details were subtle enough that they faded to the background, feeling as ordinary as turning a page in a book2.

Fin

“Don’t put all your eggs in one basket” is one of those platitudes we all grow up hearing, and in 2014, Steven & I came to truly appreciate the meaning of that expression.

Having raised our agency in Calgary meant that our largest contracts were with energy companies. Just as we began contemplating the idea of turning Blackbook into a product we could sell, the price of oil collapsed, tearing away the safety net that it had once provided us. Energy companies were quickly slashing budgets for non-essential projects.

As energy companies cut their side-projects, so did we. We no longer had time for Blackbook or other hobbies (both work-related and personal). We quickly shifted gears, funnelling our resources into finding new projects for our agency, which was now teetering precariously on the edge of survival.

Blackbook perished, but our company survived. It would be a couple years before we had the time to work on hobby apps again, during which time the marketplace became pollinated by many worthy note-taking apps. The transition to being a consumer of note-taking apps was difficult. At first, trying out a note-taking app made by someone else was accompanied by a pang of sadness, like the kind you feel when you see an ex-partner with someone else for the first time.

But time heals such wounds, and acts as a sieve for what truly matters. Even though there were some good ideas in Blackbook, it’s not certain it would have been a successful product. Part of what allowed Blackbook to be unique was that we had given it permission to be whatever it wanted to be. Had we set out to build a successful note-taking app, the result would likely have been less interesting.

Nearly a decade has passed since we sent Blackbook to the farm. A lot has changed. There are many more note-taking apps now. More importantly, the connotation of a “notes app” is evolving, and a category of “second-brain” tools has emerged.

Meanwhile, our agency took us down an interesting and profitable path. Amongst our clients, we found an overlapping desire to create digital community hubs, which we turned into B2B software for enterprise. It did well. But large companies have esoteric requirements. We would try and simplify these requirements and translate them into features that were universally useful. But eventually, the tension between its primary selling points (It can do everything! and It's well-designed and easy to use!) took a toll on us. The more complexity a product exudes, the more shapeless it becomes, and the more we become disconnected from it.

Like I said, time has a way of acting as a sieve. Partly a yearning for the days of us building things by ourselves for ourselves, and partly a reaction to our years of creating enterprise software; earlier this year we made the leap. Our daytime gig became our hobby, and our once-hobby became our daytime job.

We are once again working on a digital notebook, and this time we’re going all in on it.

Good tools disproportionately amplify input. Where would we be without levers, gears, and pulleys? Tools and frameworks for thought are much more subjective, but should still accomplish that ideal.

“Just ship it” is an expression that has become part of the zeitgeist, and for good reason. But I must say: that our initial goal with Blackbook was not commercialization allowed our process to be something more of a meditation, allowing us to discover “truths” about ourselves.

And that, perhaps, is the best reason to create your own tools and frameworks3. We shape our tools and thereafter they shape us.

- Actually, all of our side projects were things we used ourselves that had a real-life use case for our company. It was for this reason that our side projects were appealing. We could test an idea quickly by pushing an update whenever we wanted, without having to worry about downtime or breaking anything, then use those updates to determine whether to refine that work with more granularity. We experimented right within the code. We seldom made static mockups, because we could make changes directly to the codebase faster. Arriving to this version was the product of trying dozens of things, small and big, aesthetic and functional. Each one held some promise and its lessons incorporated into the next experiment. We kept pulling at various levers to symbiotically further simplicity, usability, aesthetic and reliability.

- How did we get Blackbook perform so fast? Perhaps one day I’ll write a deep-dive on this. We created our own framework from the ground-up. In a way it was easier back then, because there was this perfect equilibrium. There was just enough technology in existence for this idea to be feasible - no more and no less. There were no component-based frameworks that created virtual DOMs and then did these diff comparisons that would be computed before updating the DOM.

- Making your own tools is a fun and rewarding endeavour. We don’t know each other, but believe me when I say there has never been a better time to build your own tools. There are now technologies/components/concepts that have rendered once-complex functionality into ready-to-use ingredients. Anyone can now cook with those ingredients however they please. Cook the food you want to eat.